Who owns a melody? It’s a question not only for intellectual property lawyers but also for listeners sensitive to similarity.

Case in point: The Dukes of Stratosphear’s “Vanishing Girl” (1987), which, intentionally or not, borrows a melody with an already fraught copyright history.

Disney’s original “The Lion King” (1994) rebooted for a new generation a 1961 single by the Tokens, “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.” The song grafts simple lyrics onto an essentially wordless recording from the previous decade. And the building blocks of that song come from a 1939 recording by South Africa’s Solomon Linda — whose estate fought a long legal battle with Disney for royalties.

There are three key elements in the Linda version that inform future adaptations. For the sake of comparison, the following examples have been transposed to begin on the note C.

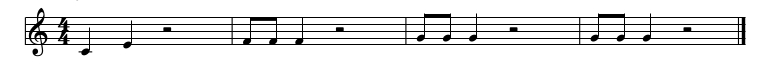

Exhbit A: “Uyimbube.”

First there’s the backing vocalists repeating “Uyimbube,” which means “You are a lion” in Zulu. Pete Seeger and the Weavers distorted this into “Wimoweh” circa 1955. Their sped-up chant has remained the foundation of other versions of the song up to the present day.

Exhibit B: Falsetto.

The next element is Linda’s high-pitched, improvised vocal line. Seeger imitates it, and it features as a wordless introduction or interlude in subsequent versions.

Exhibit C: The mighty jungle.

Finally, toward the end of the original recording (2:23), Linda’s improvisation finds approximately the melody that the Tokens later made the focus of their rendition. This is the element that interests us here, because it’s also the melody of “Vanishing Girl.”

Exhibit D: “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.”

The Tokens’ lyrics are confined to the first four notes of the major scale, and they are harmonized in the most obvious way, using the corresponding I, IV, and V chords. The wordless introduction uses the same melody, but reaches down at the end to a low fifth.

Exhibit E: “Vanishing Girl.”

The Dukes’ melody also reaches down at the end, but then climbs back up one semitone. This final note, a flat sixth, puts a twist on the Tokens’ melody, shifting it from the standard major scale to the harmonic major scale and requiring a different harmonization scheme. Instead of I-IV-I-V, it goes I-iv-I-iv. In other words, both chord progressions start in the same place, but where the Tokens proceed to a major subdominant chord, the Dukes’ subdominant is minor.

Some listeners have dismissed “Vanishing Girl” because of its similarity to “The Lion Sleeps Tonight,” perhaps forgetting that the Dukes’ whole schtick is homage and liberal borrowing from their musical forebears. Granted, the early ’60s Tokens aren’t quite of the same ilk as the late ’60s psychedelic bands the Dukes are openly emulating.

The Dukes of Stratosphear are actually the alter egos of XTC, who borrowed at least one other melody before. Frontman Andy Partridge confided in Todd Bernhardt in a 2007 interview that “Meccanik Dancing” (1978) is a condensation of “Shortnin’ Bread” (see “Complicated Game: Inside the Songs of XTC,” page 55).

Bassist Colin Moulding (aka “The Red Curtain”) wrote “Vanishing Girl.” There appears to be no public acknowledgement from him of its similarity to “Lion.” He does remark in “XTC Song Stories” (page 220): “All I had was this very smooth-sounding melody. […] So we amped it up and got the tempo going and Hollies’d it up.” Chronicler Neville Farmer refers curious listeners to the Hollies’ “King Midas in Reverse” and “On a Carousel.”

Those influences are discernable, but not nearly as explicit as the borrowed melody. Regardless, the subtle alteration and reharmonization of that melody — and the unique direction the song takes from there — make “Vanishing Girl” worthy of another listen. Whatever the melody’s provenance, it’s clear the Dukes put a unique spin on it.