This is a story about what happens when a listener, even with easy access to Spotify and YouTube, can’t instantly summon a song.

Imagine the frustration — in this day and age! — of knowing a song exists and not being able to hear it. That’s what befell me while preparing my treatise on fussing and fighting.

My research led to another alliterative pairing, Billy Blue, used in early twentieth-century “songs” about the U.S. Marine Corps. Supposedly they were songs. Multiple periodicals from the time identified them as such, but provided only lyrics, no staff notation or indication from where a tune could be borrowed. There’s no trace of any recording.

The research led to more songs about historical figures and made-up characters with the same nickname, some with neither words nor music readily available. Google could take me no further, but by that point I was determined to dox Billy Blue.

Note: Discussion of each song below includes a link to its full lyrics, with my annotations, at Genius.com.

1. Let ’em bark, for we can bite

A century before he was a leatherneck, Billy Blue was in the British navy. Admiral William Cornwallis earned the nickname “from hoisting a ‘blue peter’ (signal for sailing) the moment after he cast anchor in any port.”1

His first appearance in song is in a historical novel, published in 1887, set just after the turn of the 19th century as England feared a French invasion and Cornwallis, as commander of the Channel Fleet, worked to prevent it. A character in the book says the song is “well known to every man here, I’ll be bound.” But it’s unclear whether the lyrics are authentic to Cornwallis’ time. Probably they were invented by the novelist, R.D. Blackmore, three-quarters of a century later.

They are mustering on yon Gallic coasts,

You can see them from this high land,

The biggest of all the outlandish hosts

That ever devoured an island.

There are steeds that have scoured the Continent,

Ere ever one might say, ‘Whoa, there!’

And ships that would fill the Thames and Trent,

If we could let them go there.But England is the Ocean-Queen, and it shall be hard to do;

Not a Frenchman shall skulk in between herself and her Billy Blue.2

The book provides no musical clues beyond fife and drum accompaniment on the choruses.

Two decades later, Edward Fraser retold in ballad form a 1795 naval battle known as Cornwallis’ Retreat.3 Then a vice admiral commanding a squadron of seven ships, Cornwallis defended against and ultimately evaded a French fleet three times larger. As part of the ballad details, our hero was undaunted by the odds:

He was shavin’, so they say,

When he heard the news that day,

And his skipper came his wishes for to larn;

But he only said, ‘All right,

Let ’em bark, for we can bite,

For all they’re like to try on us, I don’t care a darn!

Billy Blue—

Here’s to you, Bill Blue, here’s to you!

2. Finger on the trigger

Billy the American marine emerged in 1900. Here he is blue because of the color of his uniform but also because he is loyal and dependable — true blue. The name Billy does not appear to refer to anyone in particular.

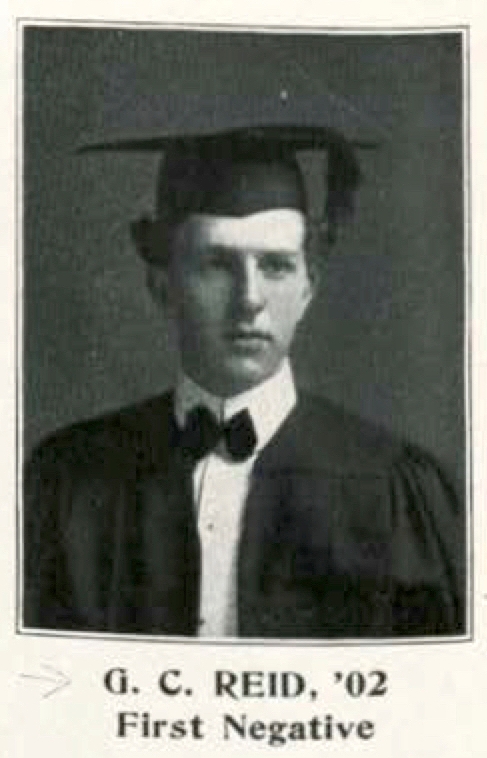

His first appearance is in the student newspaper of Washington’s Georgetown College, in a poem attributed to G.C. Reid of the class of ’02.4 The verses make reference to battles around the world involving the U.S. Marine Corps. Its first refrain ends in an unfortunate rhyme scheme:

Then it’s: Hi! get your gun, Billy Blue,

There’s going to be some fun, Billy Blue!

And it doesn’t cut a figger

If it’s “Chinee,” “Don,” or “Nigger,”

When your finger’s on the trigger, Billy Blue!5

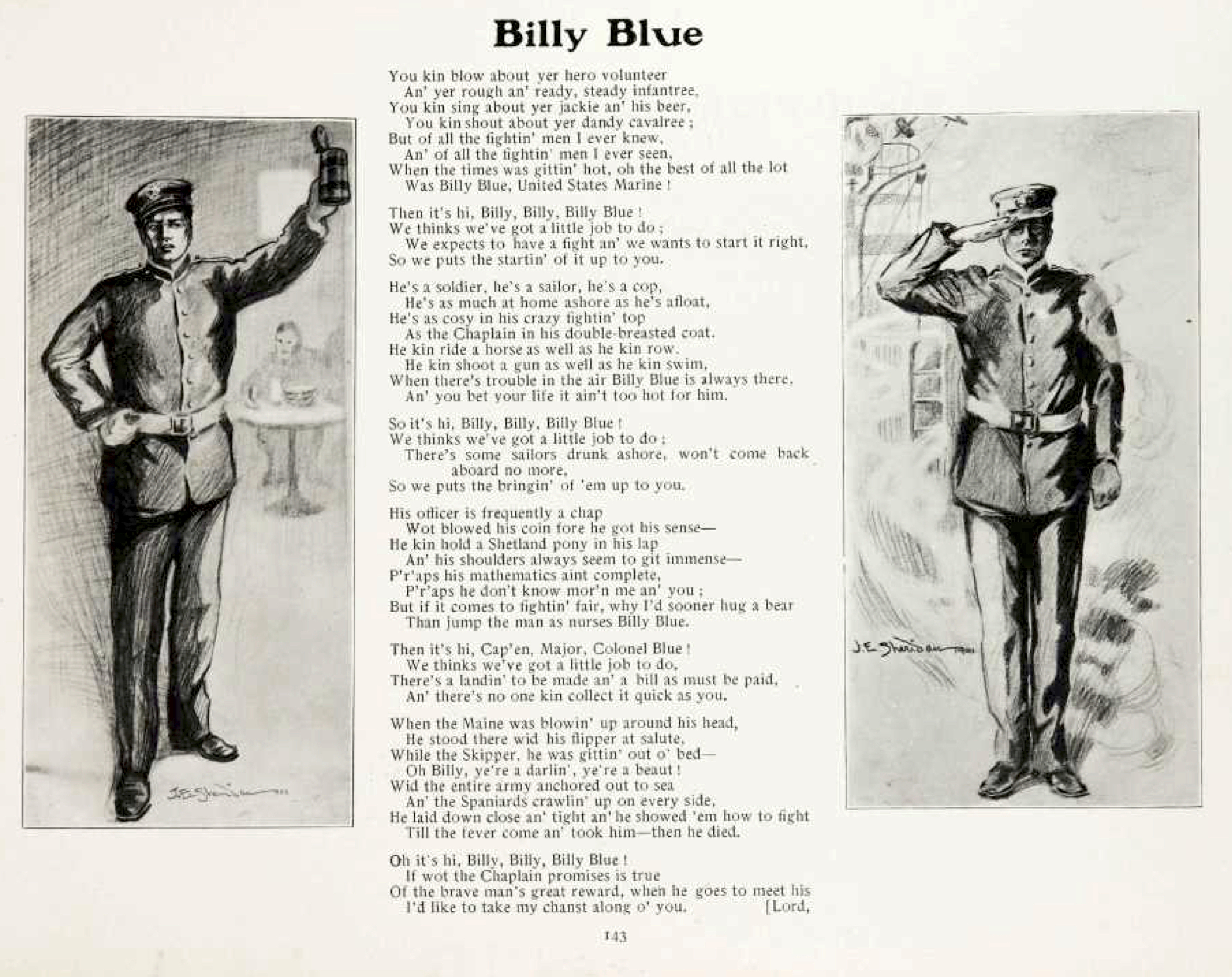

The next year the college yearbook printed, without attribution, a remarkably similar poem, rendered in low-class dialect but scrubbed of overt racial slurs. Its first refrain looks familiar:

An’ it’s hi Billy, Billy, Billy Blue!

We think we’ve got a little job to do:

We expect to have a fight an’ we want it started right,

So we puts the startin’ of it up to you.6

This version was published again, with minor revisions and under the title “The United States Marine,” in a New York magazine in 1901.7 This time it bore the name of Maurice Brown Kirby, a 1898 Georgetown graduate.

Kirby and Reid’s compositions both have refrains with AABBA rhyme schemes where the A lines are longer than the B lines. Additionally, both songs reference the explosion aboard the USS Maine in Havana Harbor in 1898, one of the inciting incidents of the Spanish-American War.8

Who can say, at this late date, whether Kirby ripped off Reid or vice versa? Perhaps Billy Blue was created collectively in the halls of Georgetown.

Both Reid and Kirby were native Washingtonians. Both published other poems in the college newspaper before and elsewhere after graduating. Neither appears to have served in the military, though one did have a marine pedigree.

George Conrad Reid, who went by his middle name, was born in 1881. He was a Georgetown man throughout his life. As an undergraduate he won the distinguished Merrick Debate Medal, arguing against the proposition that “dependent colonies would be a benefit to the United States.” He went on to earn a Georgetown law degree in 1905 and then joined the faculty as an “instructor in the law of personal property, real property and torts.” His last appearance in the yearbook is 1919.

A law school publication in 1936 said he had a “responsible position in the government service.” He remained active in alumni affairs, sometimes writing poems and songs about his alma mater, nearly until his death in 1966.

Conrad Reid was the only child of George Croghan Reid, who retired from the Marine Corps as a brigadier general. The elder Reid was also an “able lawyer,” according to his obituary. He died of a stroke in 1914. In his will he left his son a gold watch, and a grandson who bore his name received his “sword, uniforms, and commissions.”

A cousin of Conrad Reid, also named George Croghan Reid, also retired from the corps as a brigadier general. He received the Medal of Honor in recognition of the “small percentage of the losses of marines under his command” in the Battle of Veracruz during the Mexican-American War in 1914. Earlier in his career he was involved in two engagements mentioned in his cousin’s poem — the Spanish-American War and the Boxer Rebellion.

Obituaries indicate Conrad Reid had a son and a grandson who were also marines.

Maurice Brown Kirby was born in 1875. He played football for Georgetown in the days before helmets and pads, and was badly injured in a game that also saw one of his teammates killed, which may explain why he didn’t graduate until he was 23. He was also in the glee club.

In 1901 the Washington Post published another of his poems, “Skipper Schley,”9 about a Navy admiral during the Spanish-American War. In form and style it is virtually identical to his version of Billy Blue.10 A later article in the Post details how Kirby came to write it:

“Skipper Schley” is in reality the versification of a chat which Mr. Kirby had in person with one of the crew of the Brooklyn, Admiral Schley’s flagship, shortly after the battle of Santiago [off the coast of Cuba]. With the majority of his countrymen, this sailor repudiates all insinuations against his famous commander and eulogizes him in the picturesque language of the jack-tar. As Mr. Kirby has spent many years in a careful study of the United States enlisted man, his verse is not only a tribute to Admiral Schley, but an excellent portrayal of the man behind the gun.11

This article indicates Kirby set the poem to music, creating a ballad with a “martial air.” Around the same time the Washington Times gushed that the song had an “infectious swing that should place the composition among the popular hits of the day.” Here was my most tantalizing clue. Once again I could turn up no record of the actual tune.

After abandoning law school Kirby moved to New York City, writing for newspapers and magazines as well as working on Broadway. He was involved in a production of the “The Gay Hussars,” described as a “military operetta” originating in Hungary. The program cover says the work was “adapted for the American stage” by Kirby, and the lyrics to its showstopper, “Oh! You Bold, Bad Men,” are attributed to him. This song, at least, is well preserved.

The show was rushed to the stage in July 1909 in Atlantic City after rival producers threatened to put on their own version. When “The Gay Hussars” arrived on Broadway proper later that month, a New York Times critic panned it. It survived at the Knickerbocker Theater a little over a month. The show got a kinder review in Kirby’s hometown, where it played at the National Theater for a week in October.

Kirby suffered a severe head injury late one night in 1911 in New York. The Washington Post reported he was “found unconscious at the foot of a subway entrance Friday, having slipped and fallen there, the police believe.”12 Other Washington papers asserted he had been brutally mugged. In any case, he died four days later, leaving a wife and 3-year-old daughter. He was 35.

3. Go and get ’em demon

Whoever originated Billy Blue, it was Kirby’s version that endured, at least for a time. It was resurrected in 1917 when multiple newspapers, hungry for patriotic content as the United States entered World War I, reprinted it.

One paper called it the Marine Corps’ “favorite song,”13 while another asserted it “has been adopted as the song of the Corps by the Marines.”14 Individual marines or their units may indeed have sung it, but this apparently was not an official adoption. When I called the National Museum of the Marine Corps and the United States Marine Band library, neither had any record of its existence.15

Also in 1917, newspaper cartoonist Ray I. Hoppman picked up and ran with the Billy Blue concept, publishing verses following an AABBA structure virtually identical to Reid and Kirby’s, as well as recycling some of their ideas. The first stanza:

He’s a soldier and a sailor, every inch;

He’s a fighter for his country in a pinch;

And the foemen do not figure

When his finger’s on the trigger—

He’s a “go and get ’em demon,” that’s a cinch.16

The Recruiter’s Bulletin described Hoppman’s as “one of the most popular” songs about the corps, saying it “has been sung to adaptations of various popular songs.” The Bulletin that summer ran three other Hoppman poems that incorporated the nickname Billy Blue, including one more with an AABBA structure. All of them incorporated the nickname Billy Blue.

But for all Hoppman’s enthusiasm, Billy Blue evidently was never a commonly used nickname for marines. That could be because marines already had a longstanding nickname: leatherneck.

Indeed, an entry years later in a Marine Corps magazine called “Leatherneck” denigrates the Billy Blue nickname. In a passage styled after a telegram, a fictional correspondent covering a Marines vs. Army football game tells his editor:

ONE OF THE CHIEF DRUM-BEATERS FOR THE TEAM, JACK JAMES OF THE EXAMINER HERE INSISTS ON CALLING THE TEAM, “THE BILLY BLUES” OR “THE BILLY BLUE TEAM.” CONTACT POLICY AT HEADQUARTERS TO SEE IF THEY CAN’T GET HIM TO KNOCK IT OFF. THAT’S NO NAME FOR MARINE OUTFIT.17

Blue already had other, stronger associations — including with different uniformed services. Today we refer to dark blue clothes as “navy blue,” a holdover from the Royal Navy of the mid-1700s. For decades after the American Civil War, the term “boys in blue” was associated with Union Army soldiers. “Boys in blue” (or the updated “women and men in blue”) is sometimes applied to the police, a usage that goes back at least as far as 1890s England.

All of this could help explain why the Billy Blue songs never caught on, and why their melodies are likely lost to history. But their structural similarity to some other martial songs gives some clues about how they might have sounded.

One possible template or cousin is “The Monkeys Have No Tails in Zamboanga.” The lyrics follow the AABBA format and the tune, identified by one source as a “parody on an old Spanish song,” was picked up by American soldiers stationed in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War in 1899, just before the appearance of Reid’s lyrics.18 “Hinky Dinky, Parley-Voo?” aka “Mademoiselle from Armentières” also bears a resemblance and may have similar Filipino origins by way of the British Army.19

But the closest match is “Sergeant Flynn,” about the 1876 battle between the Army’s 7th Cavalry Regiment and three allied Native American tribes, popularly known as the Battle of Little Bighorn or Custer’s Last Stand.

Garryowen, Garryowen, Garryowen

In the valley of Montana all alone

There are better days to be

In the 7th Cavalry

When we charge again for dear old Garryowen.

As a nickname for the regiment, Garryowen is taken from yet another piece of music, an Irish drinking song of the 18th century that became the 7th’s official air during Custer’s time.

I learned “Sergeant Flynn” circa 1997, shouting along with other Boy Scouts at Camp Wanocksett in Jaffrey, New Hampshire. The tune employed there was recognizable to anyone who’d ever been to kindergarten: “If You’re Happy and You Know It Clap Your Hands.”20

An archival recording on the University of New Mexico Libraries website demonstrates it was sung the same way almost 50 years earlier. The performer doesn’t have the chords quite right but you get the idea.

Without specifying the melody, a retired lieutenant general attested to “Sergeant Flynn” being “particularly popular among cavalrymen in 1935 ‘when we as young lieutenants sang it at the drop of a hat with a drop of bourbon at Fort Riley.'”21 But I have been unable to determine whether “Sergeant Flynn” originated around the time of Custer’s defeat or whether it’s a more recent invention.

4. Lover, not a fighter

By the time Billy turned back up in the 1960s, he had left the military behind, trading the literal blue of his uniform for the metaphorical blue of sadness. He also became easier to hear, having been preserved on 45-rpm singles and even YouTube.

In Sammy Salvo’s 1962 treatment, Billy was a jilted lover:

In a town the size of my hometown

News good or bad soon gets around

So I guess they found out we are through

That’s why they call me Billy Blue.

The song was penned by prolific Nashville songwriter John D. Loudermilk, who had a No. 1 hit when Paul Revere and the Raiders recorded “Indian Reservation” in 1971.

If there’s any link here to the Billy Blues of old, it’s fear of French conquest. On the B-side, written by Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, Salvo sings about how he regrets giving his girlfriend a French poodle, because “she loves him better than she loves me.” The song concludes: “Don’t ever trust a Frenchman with a woman you love.”

Around the same time, Billy featured on a 45 from the obscure Ron-Cris label of Connecticut. Sonically, Sherry Connors’ “Billy Blue” is a slightly more dignified version of the Royal Teens’ “Short Shorts.” This time, Billy is the heartbreaker.

Billy, Billy, Billy Blue

I don’t know what I’m gonna do-oo-oo

You ran away with someone new-ew-ew

And now I’m left with just the blue-ue-ues

Oh Billy Blue, Billy Blue, come back I need you so

Oh Billy Blue, Billy Blue, Billy Blue

In 1970 Billy crossed back over the ocean, turning up as a Decca B side by the Dutch band Popcorn, fronted by Roek Williams. I’ve been unable to obtain a copy.

Another Dutch artist, Bruce Low, cut a “Billy Blue” single in 1979. The German lyrics (as translated by Google) tell the story of an alcoholic who gets sober after a visit from God. This recording is easy to find online; there’s even a curiously out-of-sync video of Low lip-syncing it on TV.

But why should a song sung in German feature a character with an English name? Because English is the song’s mother tongue, as penned by two more Nashville journeymen, Kermit Goell and Billy Sherrill. (Perhaps the lyrics were autobiographical for one of the writers?) Evidently the song was never recorded in English, though. The translator was Low, who was famous for teutophone adaptations of country-western songs, in particular “There’s a Bridle Hangin’ on the Wall.”

Sherrill and Goell’s only other shared writing credit is on Charlie “Silver Fox” Rich’s recording of “America the Beautiful.” The only substantial difference from the traditional patriotic anthem is a spoken intro that has the country’s major immigrant groups render the song title in their native tongues. Here is another German connection: “And in the beer halls of Milwaukee it’s ‘Vie schoen das Land.'”

Billy then kept a low profile until 1990, when he turned up as the title track on an EP by British shoegazers Faith Over Reason, an early project for singer-songwriter Moira Lambert. The lyrics seem to be describing a midnight walk with a lover.

Running in the rain but my eyes are dry

Warm in your smile, there’s no need to ask why

Your tongue on your teeth, your hand’s in my hand

Billy Blue and I are almost there, almost there

Just last year, Italian rapper Marco Sentieri released a song about bullying, written by Giampiero Artegiani, called “Billy Blu.” “[T]he song emphasizes that the phenomenon of bullying is the mirror of an increasingly life frantic, which diverts the attention of parents away from their children,” states an online article about the track.22 It says Sentieri planned an anti-bullying tour of schools that was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.

5. The spectrum broadens

A number of 20th- and 21st-century performers have used the name Billy Blue.

The only one active today is a Miami rapper. According to a press release announcing his 2012 mixtape, “His experiences are what gave him his nickname: ‘Billy’ taken from ‘Billy the Kid’ and ‘Blue’ because after his mom died he was always sad.” One of his most recent music videos, for “Hell Below,” is dedicated “in loving memory of unarmed victims of police shootings.”

Another Florida entertainer told a newspaper reporter in 1990 that his colorful stage name was literal.

Blue said he chose his stage name, Billy Blue, after performing for a time as Billy White in the White Elephant Restaurant, wearing a white tuxedo, white gloves and shoes and playing a white baby grand piano on a white fur rug. Later, he began playing a piano painted iridescent blue in a North Carolina restaurant decorated with blue [tablecloths], carpet and waitress uniforms. He decided to dress in blue and call himself Billy Blue. The name stuck.23

Playing clubs in Buffalo and Boston in the 1990s was a group called Billy Blue and the Blazers. In 2006 the frontman recorded an album called “Blues in My Room.” (“Billy blue blazes” is a phrase used to describe hellish heat, personified at DePaul University, a Catholic school in Chicago, in athletics mascot Billy Blue Demon.)

Scattered across newspaper databases are references to guitarists “Billy Blue” Graham and “Billy Blue” Mitchell, as well as to Billy Blue and Karaoke Two.

In Northern Ireland, time unknown, a Protestant singer and accordionist recorded songs like “I Am a Loyal Orangeman” and went all the way to the other side of the color wheel in choosing the moniker Billy Blue. Both colors are associated with the Orange Order (although the blue in their sashes looks purple to me). The name Billy could be a reference to King William III, remembered as a champion of the faith.

There’s even a link between Billy Blue and Johnny Cash. An act called Billy Blue cut two 45s for the Vanco label of Vancouver, Washington, probably in the early 1970s, and one side was a cover of “Folsom Prison Blues.” In the present day, a Swiss outfit called Billy Blue and the Bandits does “Folsom Prison” in its live set.

As much as I’ve learned about Billy, he’s still a mystery to me. If you know of any more songs he’s in, or have a 120-year-old music score in your attic, get in touch at zogernd [at] gmail [dot] com.

Notes

1. “Anecdote of Admiral Cornwallis.” Army and Navy Chronicle. Washington, 27 Oct. 1836, p. 259. Online: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Army_and_Navy_Chronicle_and_Scientific_R/ZKZLAAAAYAAJ. Accessed 15 July 2021.

2. R.D. Blackmore, “Springhaven: A Tale of the Great War.” New York: Harper & Brothers, 1887, pp. 243-244. Online, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7435/7435-h/7435-h.htm. Accessed 28 May 2021.

3. Fraser, Edward. “Billy Blue: A Ballad of the Fleet.” The Navy and Army Illustrated. London, 22 June 1901, p. 334. Online: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Navy_Army_Illustrated/Vc8cAQAAMAAJ. Accessed 11 June 2021. Fraser made minor revisions when he republished the poem in his 1904 history, “Famous Fighters of the Fleet.” New York: The MacMillan Co., 1904, pp. 205-211. Online: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/59423/59423-h/59423-h.htm#IV. Accessed 28 May 2021.

4. Appearing the same year was a poem by Minna Irving in which Billy Blue is a “U.S. regular soldier,” i.e., a member of the Army. Hartford Courant, 13 July 1900, p. 15.

5. Reid, G.C. “‘Billy Blue,’ U.S. Marine.” Georgetown College Journal. Washington, December 1900, p. 114. Online: https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1049758. Accessed 2 June 2021. The poem also appeared under Reid’s name in the Washington Post of 13 Jan. 1901, and in Joseph Leroy Harrison, ed., “In College Days: Recent Varsity Verse,” Boston: Knight & Millet, 1901, p. 25.

6. “Billy Blue.” The Georgetown Hodge Podge, 1901, p. 143. Online, https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/559419/gt_yearbooks_1901a_st.pdf. Accessed 3 June 2021.

7. Kirby, Maurice Brown. “United States Marine.” The Metropolitan Magazine, March 1902, p. Online: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_New_Metropolitan/0hDhxHttdYYC. Accessed 2 June 2021.

8. The explosion, and subsequent sinking of the ship, were blamed at the time on the Spanish, but may have been caused by spontaneous combustion. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Maine_(1889)#1974_Rickover_investigation.

9. Kirby, Maurice B. “Skipper Schley.” Washington Post, 4 Aug. 1901, p. 20.

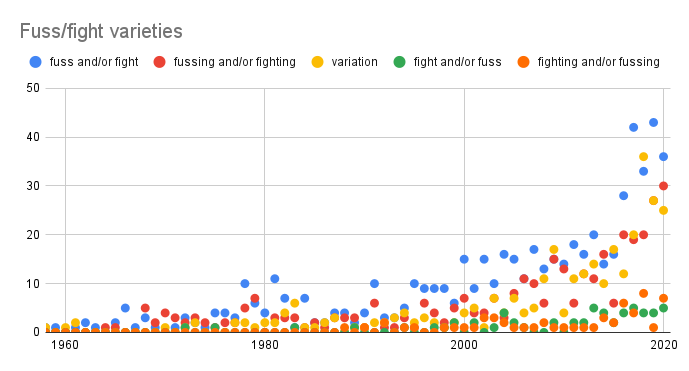

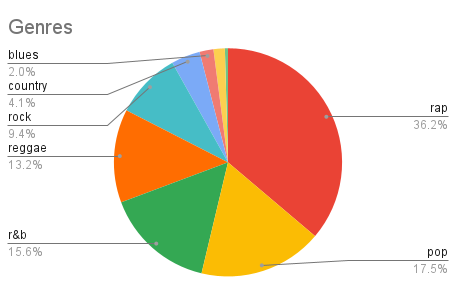

10. There are further similarities. One line, describing the humble origins of either the sailor or the marine, is substantially the same in both poems: “P’r’aps his mathermatics aint complete” vs. “We’re sure our mathematics ain’t complete.” Both songs also have fuss/fight lines: “When there’s fun or fuss or fight, / The boy to keep in sight / Is Billy Blue, United States Marine” vs. “He is better in a fight than in a fuss.” Lastly, Schley is described by his men as “truest blue.”

11. “‘Skipper Schley’ Set to Music.” Washington Post, 4 Oct. 1901, p. 2.

12. “KIRBY KILLED BY FALL: Writer Succumbs to Injuries in New York. GRADUATE OF GEORGETOWN Washingtonian Found Fatally Hurt at Foot of Subway Entrance in Metropolis. Was Author of Plays and Poems. Mother at His Side When End Comes. Wife a New York Girl.” Washington Post, 28 March 1911, p. 3.

13. Cushing, Charles Phelps. “First to fight on land or sea.” The Independent. New York, 26 May 1917, p. 372. Online: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Independent/sd9RAQAAMAAJ. Accessed 2 June 2021.

14. The Recruiters Bulletin. New York, June 1917, p. 10. Online: https://books.google.com/books?id=I0Q_AQAAMAAJ. Accessed 2 June 2021.

15. Since 1929 the official song of the corps has been “The Marines’ Hymn” (“From the Halls of Montezuma, / To the shores of Tripoli, / We fight our country’s battles / On the land and on the sea.”). It’s based on music by French composer Jacques Offenbach dating to 1867, with anonymous lyrics added later.

16. Ray I. Hoppman, “Billy Blue, Marine.” The Evening Telegram, 11 April 1917, p. 3. Online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/2004540423/1917-04-07/ed-1/?q=%22Billy+Blue%22&sp=180. Accessed 3 June 2021.

17. Gartz, Spence. “Rose Bowl ’18.” Leatherneck, Vol. 36, No. 1, 1953, p. 53.

18. Dolph, Edward Arthur. “‘Sound Off!’ Soldier Songs From the Revolution to World War II. New York: Harrar & Rinehart, 1942, pp. 64-65.

19. Ibid., p. 82.

20. A commenter on mudcat.org recalls singing “Sgt. Flynn” the same way as a Boy Scout in the 1960s.

21. Campbell, Maj. Verne D. “Armor and Cavalry Music: A Survey of Songs and Marches—and the units that rode to their strains.” Armor. Washington, March-April 1971, p. 33. Online: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Armor/yi25U18BQhcC. Accessed 3 June 2021.

22. Del Monte, Stefania. “Marco Santieri — Billy Blu, from Sanremo to school desks.” L’ItaloEuropeo. London, 7 May 2020. Online, http://www.italoeuropeo.co.uk/2020/05/07/marco-sentieri/. Accessed 3 June 2021.

23. Kirby, Sharon. “Entertainer chases away blues at nursing homes.” St. Petersburg Times, 1 Sept. 1990, p. 9. Online: infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/0EB52A6602C7D38A. Accessed 21 Sept. 2021.