Before launching this blog (seven years ago now!), I spent some time casting about for a title. I wanted to write about music, but not in the way it’s presented most places — i.e., the hottest takes on the latest tunes. I would offer my takes hesitantly at best. How to capture that?

Wikipedia’s glossary of music terminology has an entry for hesitant playing: zögernd. A better title I could not hope to find. The letter z and an umlaut? Sold.

I searched for an example of the direction used in an actual music score, but never found one. What Google did show me, however, was a few recordings of a song whose first line is “Zögernd, leise,” German for hesitantly, softly.

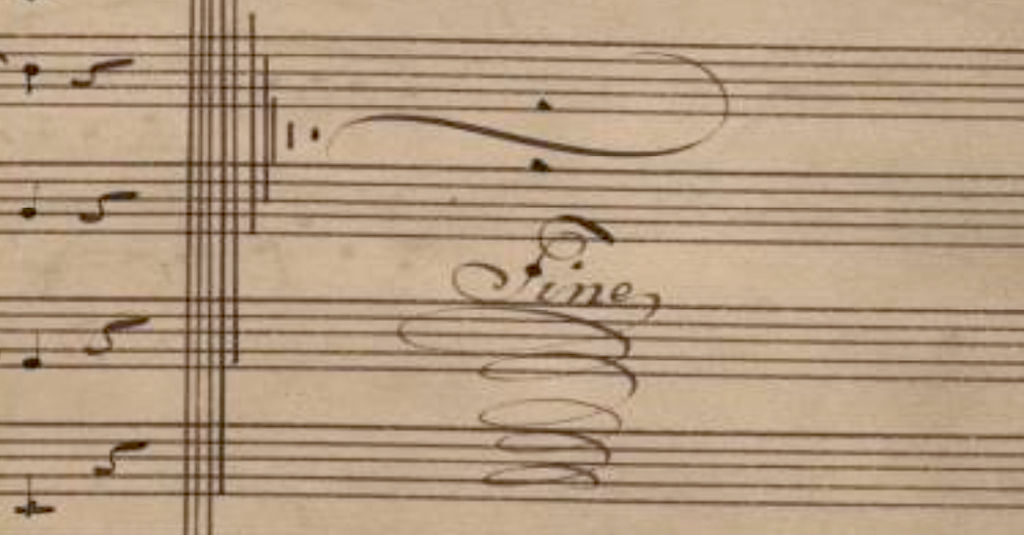

The piece, “Ständchen,” or serenade, was written nearly 200 years ago by Austrian composer Franz Schubert (born on this day in 1797). It uses an alto soloist, four-voice choir, and piano. It’s built around a poem by Franz Grillparzer. As I interpret the text (helpfully translated by Oxford Lieder), the narrator spends the song getting psyched up to serenade a sleeping love interest (“Do not sleep when the voice of affection speaks”) only to chicken out in the end (“But what in all the world’s realms can be compared to sleep?”).

The words are amusing, but it was the sounds that I fell in love with.

Here are some of the most joy-inducing melodies I’ve ever heard. Each time the soloist presents a phrase, the choir yes-ands it, and round and round they go. Somehow what they do is predictable and surprising at the same time. If Schubert were alive today, there’s no doubt he would be producing the most captivating hooks in pop music.

I’ve tried to spread the love for Ständchen in a couple ways. First as the theme song for the short-lived Zögernd postcast, where I had a computer perform all the vocal and instrumental parts using modern-day synthesizer patches.

After that, it was inevitable that Ständchen would become my next bass solo. But I hesitated. It took a few years to figure out how to pay the composition due reverence in my own irreverent musical style.

To put Ständchen within reach of the bass guitar, I transposed it down a perfect fifth, give or take an octave or two, from the key of F to the key of B flat. I also took a few small liberties in condensing material for five voices down to one — allowing the bass (which never needs to pause for breath) to sing both lead and backup. And I enlisted my trusty ICBM fuzz pedal to provide more sustain and a broader color palette than the bass alone.

So far I’ve failed to mentioned Schubert’s dazzling, frenetic-yet-placid piano writing. Surely I couldn’t pull off Ständchen without it, and so the transcription I prepared for the podcast theme became a backing track. But that wasn’t all. Biographers record that Schubert wanted his vocal works performed to a strict beat, so I bet he’d appreciate my modern drum machine treatment.

I hope you’ll agree this is a beautiful, thrilling, distinctive piece of music. There’s a good chance my rendition will not be to your taste, but I defy you to find fault with this one: