I can never remember where the downbeat is supposed to fall in the chorus of “Islands in the Stream.”

Written by the Bee Gees (brothers Barry, Maurice, and Robin Gibb), this 1983 No. 1 hit for Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers is a contender for greatest duet of all time. But I can never seem to find a stable landmass in its rushing waters. When I try to sing the titular line to myself, its cadence wriggles through my fingers like a sea lamprey migrating upriver.

Is this perceived rhythmic ambiguity a flaw in the composition? A fault in my own hearing? Whatever it is, I’ll take it as an opportunity to remix and experiment. Follow me around the room, won’t you?

When I finally sat down to analyze the chorus, I found that the downbeat coincides with the next-to-last syllable of each line.

Islands in the stream

That is what we are

No one in be-tween

How can we be wrong

Sail away with me

To anoth-er world

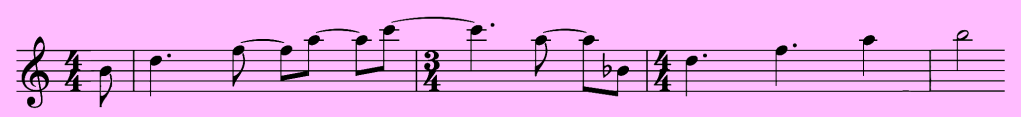

It strikes me that this phrasing emphasizes the least important part of each line — “the,” “with,” and so on. It would seem more natural to emphasize each line’s final syllable. This would require beginning each phrase an eighth note earlier.

Exhibit A: Last syllable

The emphasis could also be placed on the first syllable, using the downbeat to launch rather than conclude each line. But there’s a problem with this approach.

Following the six lines of the chorus proper is a two-line post-chorus (“And we re-ly on each other, uh-huh / From one lo-over to another, uh-huh”). Here the phrasing has no ambiguity — the emphasis falls squarely on the most important word of each line. The chorus may be movable, but the post-chorus is not. As a consequence, beginning the chorus on the downbeat doesn’t leave enough space between the two sections.

Exhibit B: First syllable

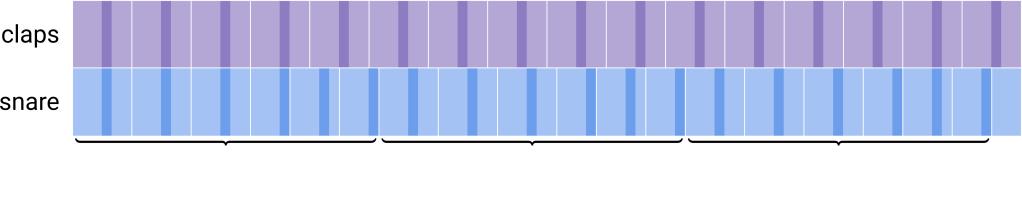

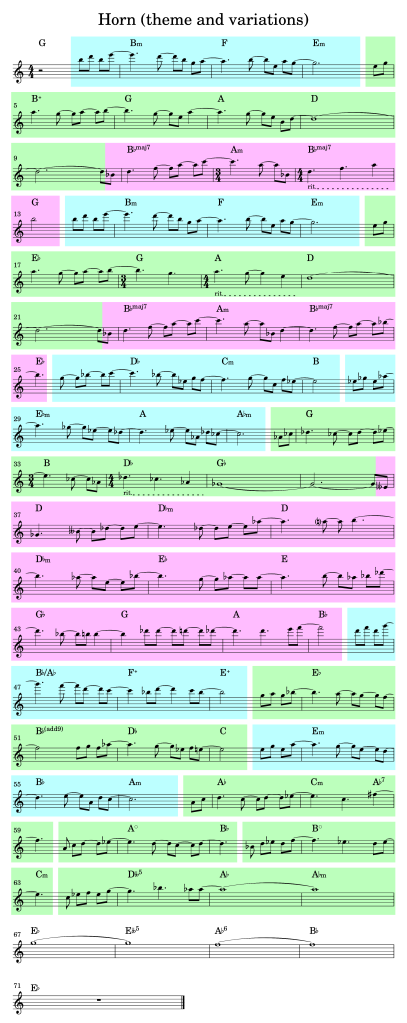

However, if we omit the post-chorus, we can shift the rest anywhere we please. Below are eight permutations of the chorus melody, each beginning one eighth note later than the previous one. To my ear, all sound equally valid, though some work better than others. If like me you were ever unclear on where the downbeat is supposed to fall, now you’ll be hopelessly confused.

Exhibit C: Variations

Isolated vocals via Dj David C., backing track via Digital Deconstructions

Exhibit A: Transcription of “Space Demons.” Listen here:

Exhibit A: Transcription of “Space Demons.” Listen here: